As sea levels rise, our salt marshes – especially around Sengekontacket Pond and Pocha Pond – are under increasing stress. But these vital ecosystems also offer powerful tools for adaptation, if we give them room to migrate and recover.

Why Salt Marshes Matter

Salt marshes are more than pretty shorelines. They deliver multiple ecosystem services that are essential for coastal communities:

- Flood and Storm Buffering: Marshes absorb wave energy and storm surge, reducing damage to buildings, roads, and humans behind them.

- Water Quality Protection: They filter runoff, trap nutrients (especially nitrogen), break down pollutants, and prevent harmful algal blooms.

- Wildlife Habitat: Nursery grounds for fish, shellfish; forage and nesting habitat for shorebirds and other species.

- Carbon Sequestration: Salt marsh soils store carbon; they also maintain soil elevation and help mitigate sea-level rise locally.

- Recreational & Aesthetic Value: Marshes contribute to the beauty of our shorelines, provide spots for birding, kayaking, clamming, fishing.

These functions make them one of the most cost-effective nature-based defenses against climate change. A recent MIT study emphasized that marshes provide coastal protection that often outperforms engineered solutions in both cost and sustainability.

The Reality on Martha’s Vineyard: Sengekontacket and Pocha Pond

Sengekontacket Pond

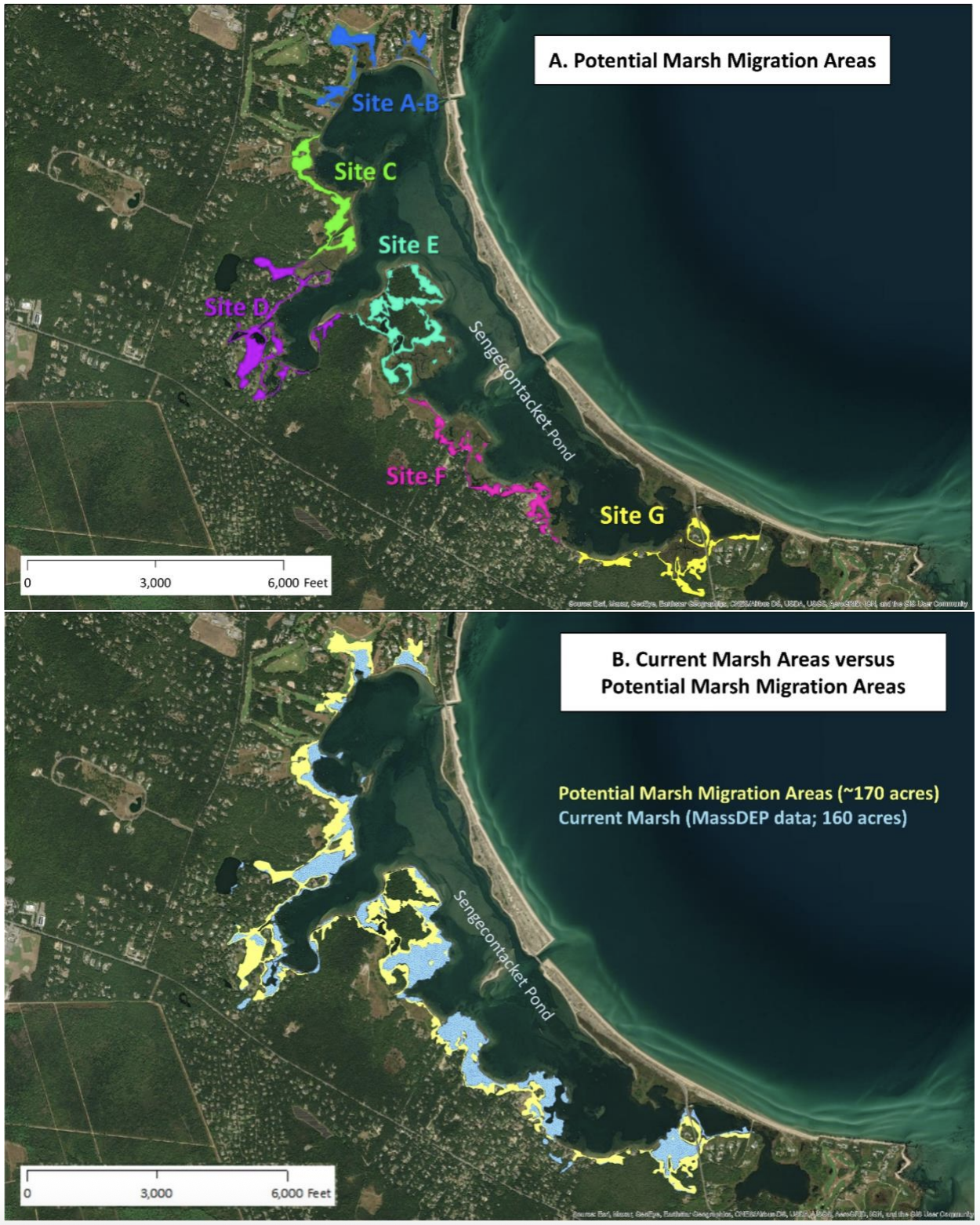

- Extent & Setting: Sengekontacket has about 160 acres of fringing salt marsh. These are not vast marsh plains like some elsewhere, but they punch above their weight in value.

- Challenges:

- Rising sea level is drowning portions of the seaward margin. Marshes need upland space to move into, but many areas are constrained by development, roads, bulkheads, seawalls. Without migration room, marshes simply sink (“drown-in-place”).

- Nutrient loading (septic systems, runoff) is stressing the pond. The marsh fringe is critical for filtering effluent.

- Economic Value: A report (“Planning for Salt Marsh Migration on the Sengekontacket Pond Shoreline,” Young/MVCC 2022) estimated that the existing salt marsh provides benefits on the order of $10,871 per acre per year from services such as storm damage reduction, fisheries, and water quality. That amounts to roughly $1.74 million annually for the community from the marsh as it exists today.

Pocha Pond

- Physical Characteristics: The watershed is about 921 acres; the pond itself is 210 acres. It’s shallow — mean depth ~2.5 feet — and has a tidal range of ~1.9 feet.

- Water Quality & Impairment: Pocha Pond is currently classified as “impaired.” Historically, it did not support eelgrass. Total organic nitrogen load is high. These are warning signs.

- Vulnerability: Shallow ponds with impaired water quality are more sensitive to stressors like higher water temperatures, increased nitrogen, and reduced oxygen—factors tied to climate change and also local land use. Also, with limited depth, flooding and salt-water intrusion can shift pond ecosystems rapidly.

What Salt Marsh Migration Means—and What Must Change

“Migration” in this context means that as sea level rises, marsh zones move inland — the high marsh retreats upland, low marsh floods more often, etc. But migration only works if:

- Space is available upland. Where upland is blocked by development or infrastructure, marshes may have nowhere to go and drown.

- Land-use planning and zoning take into account marsh migration corridors. That might mean purchasing or securing easements on land behind marshes, restricting development in critical zones.

- Restoration efforts (living shorelines, sediment augmentation, stabilizing eroded edges) are employed where practical to preserve existing marsh and support its migration.

- Water quality management, especially regarding nitrogen loading from septic systems, runoff, etc., so marshes do not lose function even before physical loss.

In the Sengekontacket study, several options were put forward: mapping septic systems, monitoring groundwater, buyouts of properties in migration zones (or at least structures), easements or donations of upland lands, and adjustments to bylaws.

Local Actions & Success Stories

- Living Shoreline Projects: On Sengekontacket, coir logs (bundles of coconut fiber) have been used to trap sediment and stabilize eroding banks, allowing Spartina grasses and other native vegetation to reestablish.

- Policy & Planning: The Martha’s Vineyard Commission and related bodies are producing reports and mapping potential migration zones, estimating loss under different scenarios, and urging communities to integrate these findings into land use regulation.

Risks If We Don’t Act

- Loss of marsh area, meaning less flood protection. Homes, roads, infrastructure will face more damage and higher costs.

- Declining water quality, more frequent algal blooms, loss of swim and shellfishing areas.

- Loss of habitat for wildlife: shorebirds, fish, invertebrates.

- Cultural and aesthetic loss: marshes are part of the Vineyard’s identity.

What YOU Can Do

- Support efforts to preserve upland areas adjacent to existing marshes.

- Advocate for stronger zoning and bylaws that limit construction in migration zones.

- Maintain or upgrade septic systems; reduce fertilizer usage and runoff.

- Support restoration and living shoreline efforts.

- Engage with local planning and conservation organizations to push for marsh-friendly policies.

Conclusion

Salt marsh migration isn’t just a technical ecological concept—it’s an imperative for preserving the resilience of Martha’s Vineyard. With foresight, planning, and care, we can help Sengekontacket, Pocha Pond, and other marshes adapt. When we protect them, we protect ourselves: our homes, our ponds, our biodiversity, and our way of life.

Further Reading

- Story Map: Wetland Migration on MV

- Preserving Salt Marsh as Sea Level Rises: Sengekontacket Pond Case Study

- Planning for Salt Marsh Migration on the Sengekontacket Pond Shoreline

- Islanders Ponder How to Handle Rising Tides

- Salt Marsh Restoration Aims to Protect and Monitor Key Habitat

- Trustees restoring Chappy marsh

- Study: Marshes provide cost-effective coastal protection